What this Briefing adds

- The HPV vaccine is highly effective with an excellent safety profile. It has reduced genital warts and is preventing cervical cancer. The potential to eliminate cervical cancer and other HPV-related cancers (eg, head and neck cancers) beckons.

- The vaccine was initially introduced with a 3-dose schedule, but new evidence shows one vaccine dose is adequate; already adopted by the UK and Australia.

- It took three years for NZ to change from 3-dose to a 2-dose schedule for HPV vaccine. Delaying the change to a 1-dose wastes tax-payer funds and health resources for limited, if any, benefit.

Implications for policy and practice

- Immunisation policies must be based on science, and not constrained by out-dated vaccine manufacturer datasheets.

- With a single dose, it becomes more feasible to set and achieve a 90% coverage target that can eliminate HPV-related cancers.

- Promotion of the vaccine becomes easier when only one dose is needed; ongoing efforts are needed to promote the vaccine and address misinformation.

Author details

Dr Oz Mansoor, Medical Officer of Health, Tairāwhiti (on sabbatical with the Public Health Communication Centre)

Prof Nikki Turner, Department of General Practice and Primary Care, University of Auckland, and Medical Director of the Immunisation Advisory Centre

Prof Nick Wilson, Department of Public Health, University of Otago Wellington, and Public Health Communication Centre

Prof Michael Baker, Department of Public Health, University of Otago Wellington, and Public Health Communication Centre

Appendix 1: Human papillomavirus (HPV) and its vaccine

It looks like the virus, but this is an image of the vaccine from its co-inventor.10 The vaccine is made of L1 protein. This is one of two proteins that are the virus 'coat'. As it does not contain the DNA of a virus, it cannot infect. But it looks so much like the virus, it makes the vaccine work really well.

How do we make the proteins come together just like the virus? It’s biology! They just naturally form (‘self-assemble’) into a set of five (pentamers) and 72 of these form a 20-sided shell

Several viruses are known to cause cancer. Human papillomavirus (HPV) causes the most. In 2018, 4% of all new cancers globally were HPV-related,11 down from 4.5% in 2012.12 In this appendix, we provide more details on the vaccine and its impact to date in preventing genital warts and cancer; and the cancer burden it can prevent.

HPV vaccine: from four to nine types

There are over 200 types of HPV, over 40 infect genital areas. Of these, 14 types are defined as ‘high-risk’ for causing cancer: HPV16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 66 and 68. The ‘low risk’ types rarely cause cancer, but some (6, 11, 42, 43, 44) cause warts on or around the genitals, anus, mouth, or throat (about 90% from types 6 and 11). When warts form in the larynx or respiratory tract (respiratory papillomatosis) these can cause breathing problems.

The HPV vaccine first used in NZ had 4 types: 6, 11, 16, and 18. The first two cause about 90% of anogenital warts; the second two about 70% of cervical cancers and most other HPV-cancers. Since 2017, we have used nonavalent (ie, has 9 types) HPV vaccine that has five more high-risk HPV types, to cover 90% of cervical cancers.

HPV vaccine safety

Various adverse events following immunisation (AEFIs) with HPV vaccine have been highly publicised. The data and studies that fail to find the safety concern, not so much. Lack of trust is a related factor, fueled by disinformation.

An AEFI is indeed any event that occurs after immunisation. But these can be coincidental rather than being caused by the vaccine. A review of randomised studies found over a third had some health event after either vaccine (35%) or placebo (36%).13 These events that follow equally after vaccine or placebo are coincidental that can be falsely blamed on the vaccine.

The WHO’s Global Advisory Committee on Vaccine Safety (GACVS) has reviewed HPV vaccine safety several times, most recently in 2017. Aside from a risk of anaphylaxis in about 1.7 per million doses, and injection reactions including fainting (a common anxiety or stress-related reaction), no other adverse reactions have been identified. The GACVS concludes that “despite the extensive safety data available for this vaccine, attention has continued to focus on spurious case reports and unsubstantiated allegations... that have a demonstrable negative impact on vaccine coverage in a growing number of countries, and that this will result in real harm.”

These findings are reinforced by reviews by the American Autonomic Society14, a Cochrane Review of randomised trials15, and a narrative review of 109 studies.16

HPV vaccine efficacy and impacts

In the initial studies, vaccine efficacy was 95% or higher in preventing persistent infection, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) 2/3, and adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS).4

The Cochrane Library summarises the evidence for ‘at least one dose’ of HPV vaccine protecting against HPV16/18 pre-cancer and localised cancer of the cervix as ‘high‐certainty’ and ‘moderate‐to high‐certainty’. A 14 year follow-up study found no cases of pre-cancers from HPV16/18 in Nordic women, with no evidence of waning immunity over this time period.17

Data on preventing cervical cancer are just emerging. A Scottish study reported no cases of invasive cancer in women aged 24 to 32 years who had who received one or more doses at age 12 or 13 years of age.2 Those given three doses at 14 to 22 years of age had cancer incidence: 3.2 vs 8.4 per 100,000 women who had no vaccine.

In Sweden, analysis of national register data on over 1.5 million females aged 10 to 30 years of age from 2006 through 2017 reported the vaccine 88% effective against invasive cervical cancer in those immunised under the age of 17 years.18

In England, a registry-based retrospective cohort study of 20-29 year old women reported 87%, 62% and 34% reductions in cancer incidence for those vaccinated at ages 12-13, 14-16, and 16-18 years, respectively.19

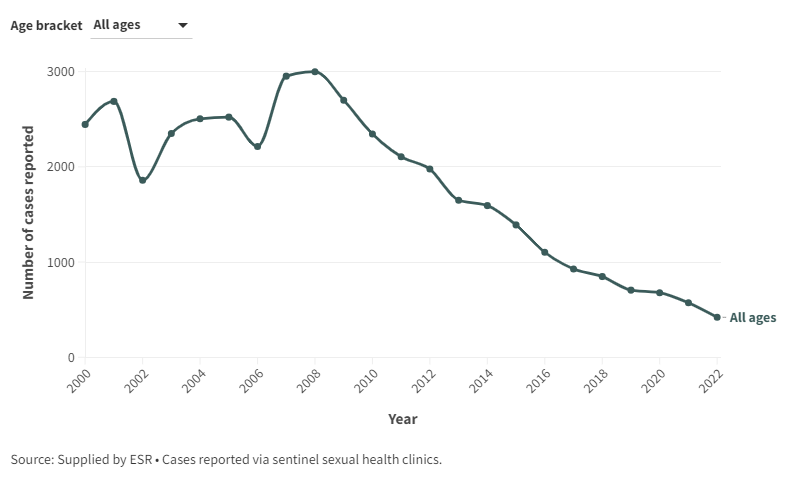

The impact on genital warts was immediately apparent. A systematic review reported HPV vaccine leading to up to 90% reduction in HPV 6/11/16/18 infection and genital warts.20 The USA CDC report that genital warts declined by 88% and 81% among teen girls and young adult women, respecitively, compared to 2006 when the vaccine was introduced. In NZ, there continues to be a decline in in the reported incidence of genital warts. (Figure A1).

Figure A1: Number of genital warts cases reported at selected sentinel sites, 2000-2022

New Zealand cancers

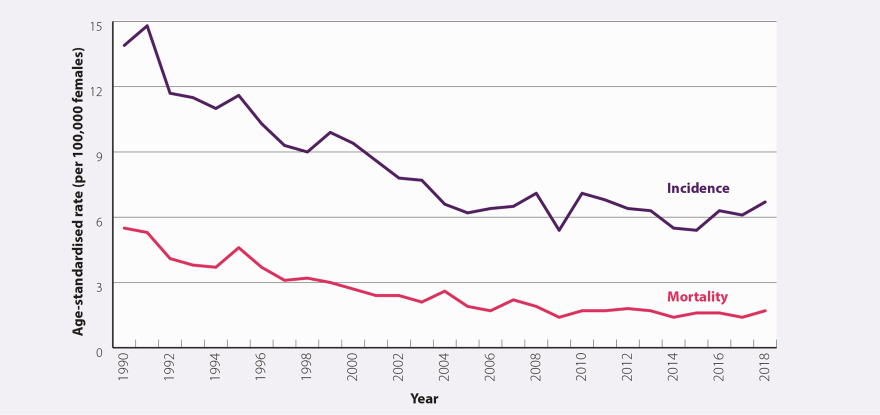

Analysis of cervical cancers in those born from 1990, the oldest vaccine-eligible females, has not been published for NZ. Cervical cancer incidence has been increasing since 2015, suggesting other factors are increasing incidence, while the declines from cervical screening had plateaued before the start of the programme in 2008 (Figure A2).

Figure A2: Age-standardised incidence and mortality rates (per 100,000 females) for cervical cancer between 1990 and 2018 in New Zealand. Source: bpacnz

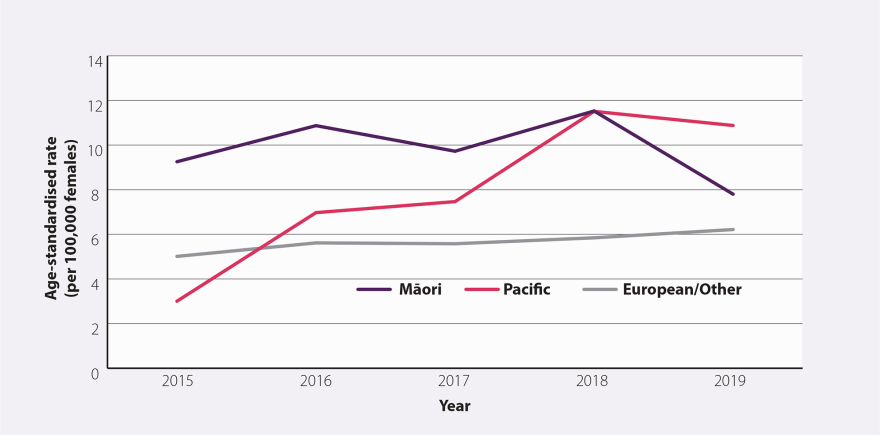

The dip in 2009, the year after the start, is transient, suggesting a possible data issue. There seems to be a rise in incidence from 2015. The equity gap in cervical cancer, results from lower screening rates (Figure A3). Another inequity is that Māori have under double the incidence of cervical cancer, but over double (2.7) times the mortality.4

Figure A3. Age-standardised incidence rate (per 100,000 females) for cervical cancer by ethnicity between 2015 and 2019 in New Zealand. Source: bpacnz

Other cancers caused by HPV

There are no data on the impact of HPV vaccine on other cancers, but it is expected to prevent “about 69% of vulvar, 75% of vaginal, 63% of penile, 90% of anal and 70% of oropharyngeal cancers.”4 Immunisation Handbook, Table 10.2 of the Handbook shows the incidence of 2017 HPV-related cancers, with most oropharyngeal cancers in the tonsil, and most of them in men:

Table 1. Number and age-standardised rate (per 100,000) of HPV-associated cancers (excluding cervical), NZ, 20174

| Anatomic site | Number | Rate registrations

(per 100,000) |

|---|

| Vulva | 52 | 1.2 |

| Vagina | 19 | 0.5 |

| Penis | 18 | 0.5 |

| Anus | | |

| 40 | 1.1 |

| 21 | 0.6 |

| Oropharynx | | |

| 4 | 0.1 |

| 10 | 0.3 |

| Tonsils | | |

| 21 | 0.6 |

| 85 | 2.7 |

Appendix 2: HPV immunisation coverage in NZ

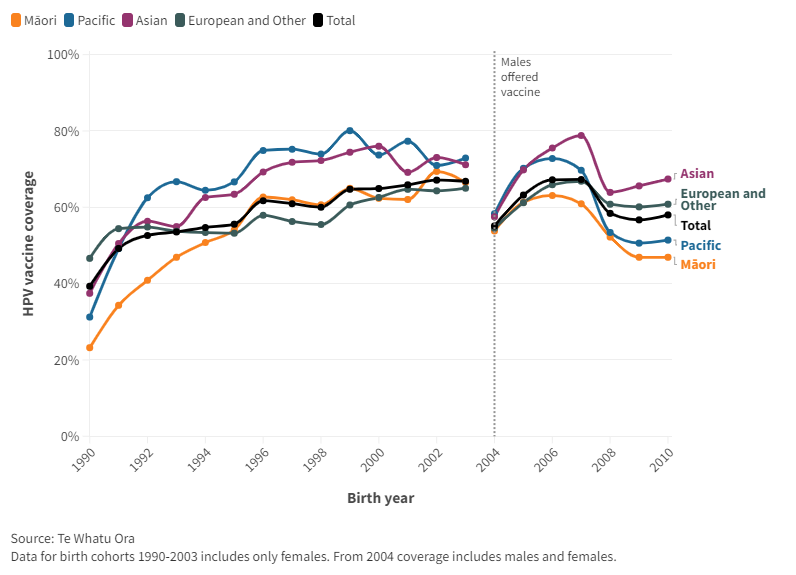

HPV coverage is reported by birth cohort for females only until 2004 birth cohort. Coverage had been slowly improving until 2019 (2007 birth cohort), but dropped during the Covid-19 pandemic and may be recovering now (Figure A4).

Figure A4: HPV vaccine coverage by birth cohort and ethnicity

The dip in coverage for the 2004 cohort reflects their age in 2017 when males became eligible (aged 13 years versus 12 years for most). But from the 2006 birth cohort, coverage for both sexes is practically the same.

The apparent negative ‘equity gap’ (1996 to 2003 birth cohorts) contrasts to that of childhood immunisation, though Asian ethnicities have the highest coverage for both. The equity gap for Māori emerges again with the pandemic (2008 cohort onwards), although remains smaller than in childhood immunisation.

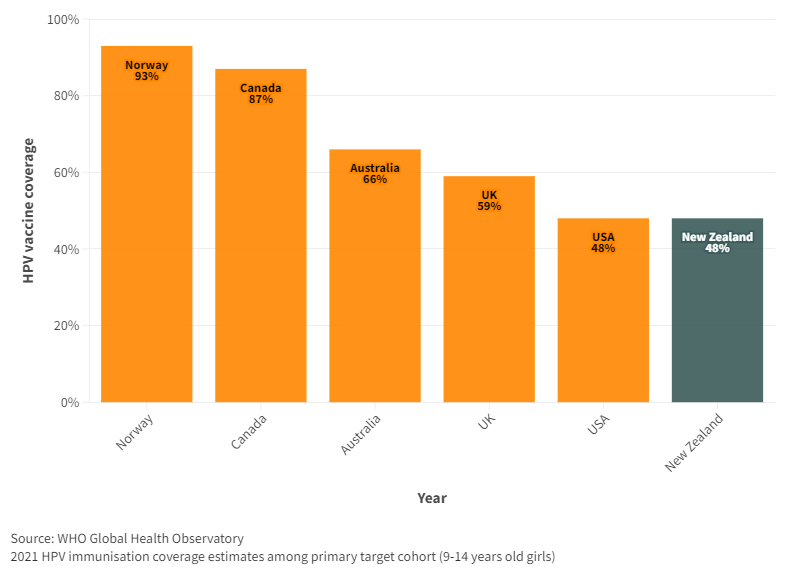

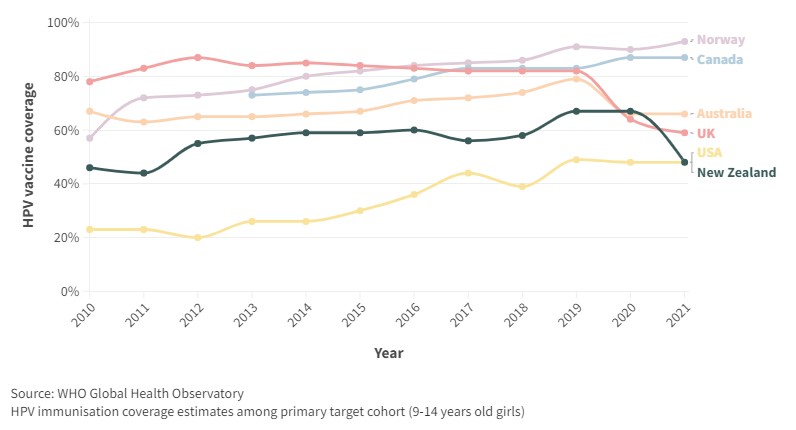

WHO monitors HPV coverage in 9-14 year females. For the latest year, 2021, NZ had lower coverage than Australia, UK and many developing countries. Even the USA, with a lower coverage previously, matched that of NZ in 2021 (Figure A5).

Figure A5. HPV coverage, by year for New Zealand and selected countries