Summary

The Government, and almost everyone considering how to achieve a Smokefree Aotearoa, agrees that nicotine and tobacco products should be regulated proportionate to the harm that they cause. However, following repeal of the previous Government’s smokefree measures, regulation is now disproportionate to risk as, in many important areas, smoked tobacco products have weaker regulation than vaping products. The Government must urgently address its espoused commitment to risk proportionate regulation by introducing regulations to greatly restrict the availability, appeal, and addictiveness of smoked tobacco products. At the same time, they must implement robust policies to protect young people from addiction to alternative nicotine and tobacco products.

This Briefing analyses how smoked tobacco and vaping products could be regulated with a risk proportionate approach in Aotearoa New Zealand.

Risk proportionate regulation requires regulation of consumer products proportionate to the harm they cause individuals and communities. The issue has become more salient following the introduction of new nicotine products like e-cigarettes and vapes which will likely cause fewer physical harms than smoked tobacco, though will nonetheless cause harm through addiction.

In Aotearoa, major health groups agree smoked tobacco and vaping products should be subject to risk proportionate regulation.1, 2 International researchers, leading Māori health organisations (e.g., Hāpai te Hauora) and the Ministry of Health have issued similar calls. In recent Cabinet papers on youth vaping and heated tobacco products, the Associate Health Minister committed to proportionate regulation (see Appendix for quotes), as have the tobacco industry and its allies.

Despite this shared view, proposals on how to achieve risk-proportionate regulation vary greatly. Tobacco companies promote minimal regulation of vaping products while the vast majority of health groups urge far stronger regulation of smoked tobacco products,3 whilst still stressing the need to protect young people from becoming addicted to any nicotine-containing product.

The Smokefree 2025 goal adopted by the National Party-led Government in 2011, took the latter approach and aimed to reduce smoking prevalence among all population groups and reduce tobacco availability to minimal levels by 2025.1 The Smokefree Aotearoa 2025 Action Plan2 and the Smokefree Environments and Regulated Products Amendment Act (SERPA) introduced in 2022 by the Labour-led Government followed the same logic and introduced much stronger regulation of smoked tobacco products, including mandatory denicotinisation, greatly reduced retailer numbers, and a smokefree generation policy (albeit this legislation has since been abandoned).

So is regulation in Aotearoa risk proportionate for tobacco and nicotine products?

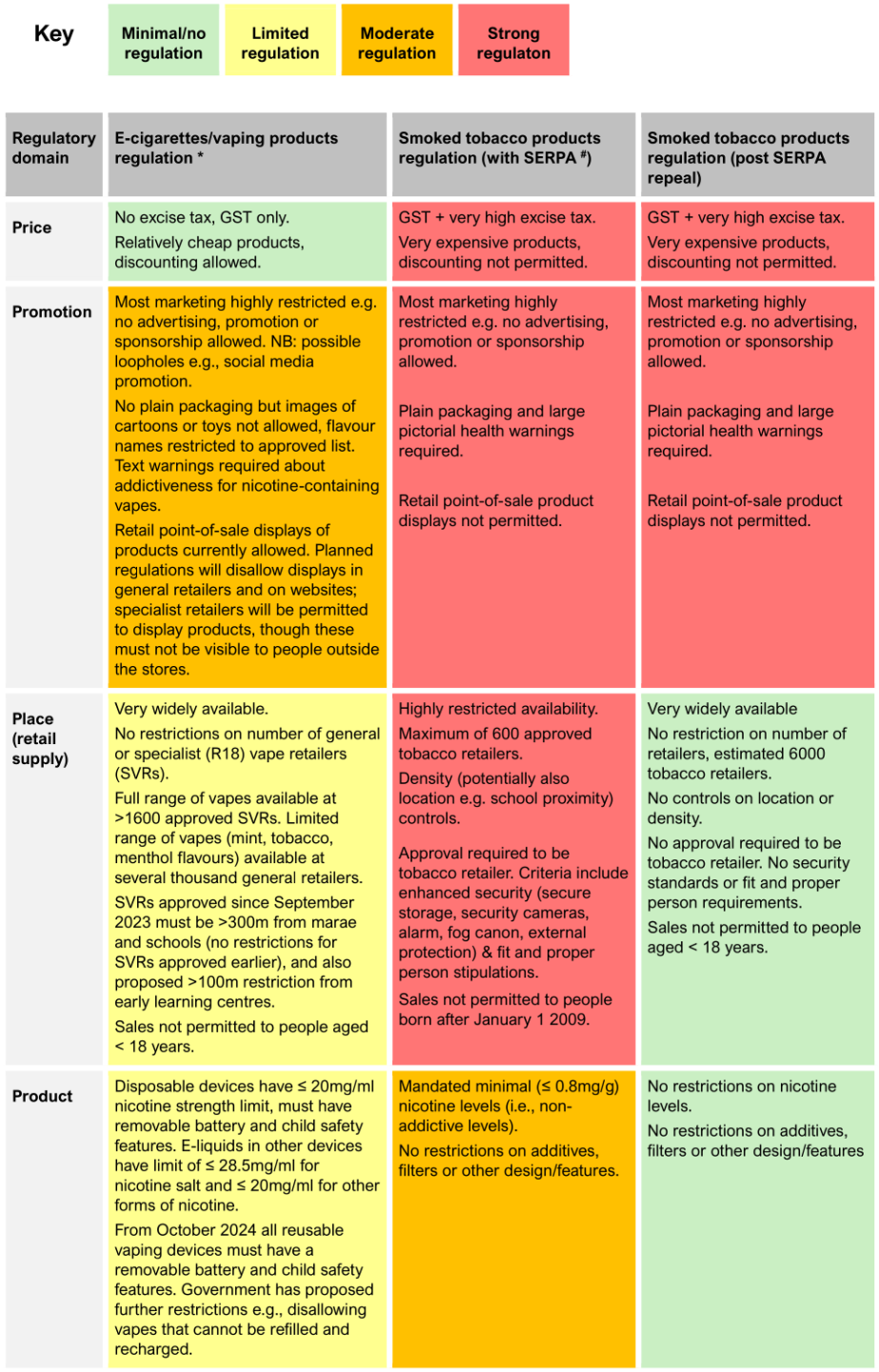

We investigated this question by comparing the strength of regulation of smoked tobacco products and vaping products in relation to price, promotion, accessibility, and product constituents and design. We considered risk in relation to physical harm, assuming that for risk proportionate regulation to be present smoked tobacco products should be regulated more stringently than vaping products. We made the comparison for current or pending regulations and in a scenario where measures introduced in SERPA had been implemented rather than repealed (see table).

Regulation of price (Risk-proportionate)

Regulation of price is highly risk-proportionate. The main price regulatory measures are excise taxes and GST; the latter applies to all nicotine and tobacco products but excise tax is applied only to smoked tobacco products. From 2011-2020, annual 10% plus inflation tobacco excise increases resulted in cigarettes in Aotearoa being among the most expensive in the world. Price differentials are further increased because discounting is allowed for vapes but not smoked tobacco products, with some disposable vapes available at pocket money prices.

Regulation of promotion (Partially risk-proportionate)

Regulation of promotion is partially risk-proportionate. Strict controls (largely bans) apply to advertising and sponsorship of smoked tobacco and vaping products. Point-of-sale displays and packaging are more strongly regulated for smoked tobacco products (e.g., plain packaging is required and point-of-sale displays are not allowed).

Vaping products use branded packaging, though this may not feature cartoon or toy imagery, or use fanciful flavour descriptors. Retailers may display products (though this practice may soon be disallowed in general retailers). However, social media promotion of vaping products circumvents marketing restrictions, and very high youth vaping prevalence suggests further restrictions are required.

Regulation of retail access (Disproportionate)

Regulation of retail accessibility is currently mostly disproportionate to risk. While the same age restrictions (18 years) apply to both products, retailers are not required to register or meet any criteria to sell tobacco products, and the number, density and location of tobacco retailers remains unregulated.

There is limited regulation of retailing of vaping products; for example, general retailers (e.g., dairies) may only sell three flavours of vapes, specialist vaping stores (SVRs) must be registered, and new SVRs (existing stores are exempt) may not open within 300m of marae and schools.

Product regulation (Highly disproportionate)

Product regulation is currently strongly disproportionate to risk. Smoked tobacco products are unregulated regarding constituents (nicotine strength, additives and flavours) or design features (e.g., filters, filter ventilation, filter flavour capsules). This approach allows the tobacco industry to manipulate constituents and design to maximise the addictiveness, palatability and appeal of their products. Research indicates that regulating these attributes6, 7 will likely reduce smoking uptake by youth and encourage people who smoke to quit.

By contrast, nicotine strength of vaping products is modestly restricted and limited regulation of design features has recently been implemented (e.g. requirements for removable batteries and child locks) or are planned (e.g., ban on disposable vapes ).

Reduced risk-proportionality following repeal of smokefree legislation

The table below shows that the repealed SERPA measures would have created risk-proportionate regulation of the accessibility and addictiveness of smoked tobacco products relative to vaping products, by greatly decreasing retailer numbers and minimizing the nicotine content of cigarettes and other smoked tobacco products.

Table: Key features of regulation of smoked tobacco and vaping products currently and in scenario of non-repeal of the 2022 Smokefree Environments and Regulated Products Amendment Act measures.

*For simplicity we have ignored therapeutic nicotine products such as patches and gum, and also other alternative products such as heated tobacco

#Smokefree Environments and Regulated Products Amendment Act 2022

Conclusions

Sixty years after the US Surgeon General’s report presented unequivocal evidence that smoking is extremely harmful to health, highly disproportionate regulation of the constituents, design and retail availability of smoked tobacco products persists. These products remain widely accessible, despite the NZ Government’s goal of achieving ‘minimal availability’ by 2025.1 Tobacco companies remain free to develop highly addictive, palatable and appealing products, including cigarettes with: high nicotine content, design features and additives to maximise addictiveness and make tobacco smoke less harsh and easier to inhale, and add flavour capsules that appeal preferentially to young people.3 4

Meanwhile initially permissive regulation of vaping products has resulted in very high levels of youth vaping and harms due to addiction. The Government has responded by proposing additional measures to protect youth from vaping. Further measures are very likely to be required in future.

However, the Government has no proposals to strengthen regulation of smoked tobacco products, so the current areas of grossly disproportionate regulation are set to continue. Given there is no dispute that smoked tobacco products cause immense harm, particularly for Māori, we call on the Government to introduce measures that will greatly restrict the accessibility, appeal and addictiveness of smoked tobacco products. Doing so will rectify current regulatory anomalies and deliver on the goal adopted by the National Government in 2011.

What this Briefing adds

- There is broad consensus for risk-proportionate regulation of tobacco and other nicotine delivery products like vapes.

- Repeal of the previous Government’s smokefree measures created highly risk disproportionate regulation of smoked tobacco, particularly its accessibility and product attributes.

Practice and policy implications

- The NZ Government should urgently implement proper risk-proportionate regulation by restricting the accessibility and reducing the appeal and addictiveness of smoked tobacco products.

- The NZ Government should also further tighten regulations to protect young people from addiction to all other nicotine containing products.

Authors details

Prof Richard Edwards, Co-Director of ASPIRE Aotearoa Research Centre, and Department of Public Health, Ōtākou Whakaihu Waka | University of Otago

Prof Janet Hoek, Co-Director of ASPIRE Aotearoa Research Centre, and Department of Public Health, Ōtākou Whakaihu Waka | University of Otago

Assoc Prof Andrew Waa, Co-Director of ASPIRE Aotearoa Research Centre, and Department of Public Health, Ōtākou Whakaihu Waka | University of Otago

Prof Nick Wilson, Co-Director, Public Health Communication Centre, and Department of Public Health, University of Otago Wellington

Appendix: Statements on risk proportionate regulation in Cabinet Papers

Casey Costello, Cabinet Paper: Reducing excise duty from Heated Tobacco Products, May 20 2024

10. …… The report back will also include advice on a risk proportionate regulatory regime to protect non-smokers from the harms of any new products made available to support smokers to quit.

Casey Costello, Cabinet Paper: Smokefree 2025: Cracking Down on Youth Vaping, 23 May 2024

9. This paper is part of the Government’s broader work programme to achieve Smokefree 2025, which focuses on:

9.1 reducing the harm from tobacco by supporting smokers to quit smoking and preventing our young people from smoking;

9.2 cracking down on vaping amongst young people;

9.3 implementing a regulatory regime that manages harm in a proportionate way to achieve the broader objectives; and

9.4 strengthening the range of non-regulatory interventions available for those groups most at risk. [...]

50. I want to ensure proportionality across the various products that are regulated under the Smokefree Environments and Regulated Products Act 1990. Smoked tobacco is the most harmful product and I have asked officials for advice on what further regulatory steps could also be undertaken for smoked tobacco to ensure consistency across the suite of regulated products.