References

- Ministry of Health. Tier 1 statistics 2018/19: New Zealand Health Survey. 2019. (14 November). https://www.health.govt.nz/publication/tier-1-statistics-2018-19-new-zealand-health-survey.

- Connor J, Kydd R, Maclennan B, Shield K.Alcohol-attributable cancer deaths under 80 years of age in New Zealand. Drug and Alcohol Review 2017;36:415-23. doi: 10.1111/dar.12443.

- Connor J, Kydd R, Shield K, Rehm J.The burden of disease and injury attributable to alcohol in New Zealanders under 80 years of age: marked disparities by ethnicity and sex. New Zealand Medical Journal 2015;128:15-28.

- Nana, G. (2018). Paper presented by Ganesh Nana. Alcohol Action Conference 2018: Who should pay for all the harm from alcohol?, Te Papa, Wellington, 15 August.

- World Health Organization. Global status report on noncommunicable diseases 2010. 2011. http://www.who.int/nmh/publications/ncd_report2010/en/.

- Jernigan D, Noel J, Landon J, Thornton N, Lobstein T.Alcohol marketing and youth alcohol consumption: a systematic review of longitudinal studies published since 2008. Addiction 2017;112:7-20.

- Anderson P, de Bruijn A, Angus K, Gordon R, Hastings G.Impact of alcohol advertising and media exposure on adolescent alcohol use: a systematic review of longitudinal studies. Alcohol and Alcoholism 2009;44:229-43.

- Rapsey CM, Wells JE, Bharat MC, Glantz M, Kessler RC, Scott KM.Transitions Through Stages of Alcohol Use, Use Disorder and Remission: Findings from Te Rau Hinengaro, The New Zealand Mental Health Survey. Alcohol and Alcoholism 2018;54:87-96.

- Brown K. Association Between Alcohol Sports Sponsorship and Consumption: A Systematic Review. Alcohol and alcoholism (Oxford, Oxfordshire) 2016;51:747-55.

- Health Promotion Agency. Cutting back on alcohol consumption: Key results from the 2015/16 Attitudes and Behaviour towards Alcohol Survey & 2016 Health and Lifestyles Survey. Wellington, New Zealand: Health Promotion Agency, 2018.

- Babor TF, Robaina K, Noel JK, Ritson EB.Vulnerability to alcohol-related problems: a policy brief with implications for the regulation of alcohol marketing. Addiction 2017;112:94-101.

- Casswell S, Huckle T, Wall M, Parker K, Chaiyasong S, Parry CDH, Viet Cuong P, Gray-Phillip G, Piazza M.Policy-relevant behaviours predict heavier drinking and mediate the relationship with age, gender and education status: Analysis from the International Alcohol Control Study. Drug and Alcohol Review 2018;37:S86-S95.

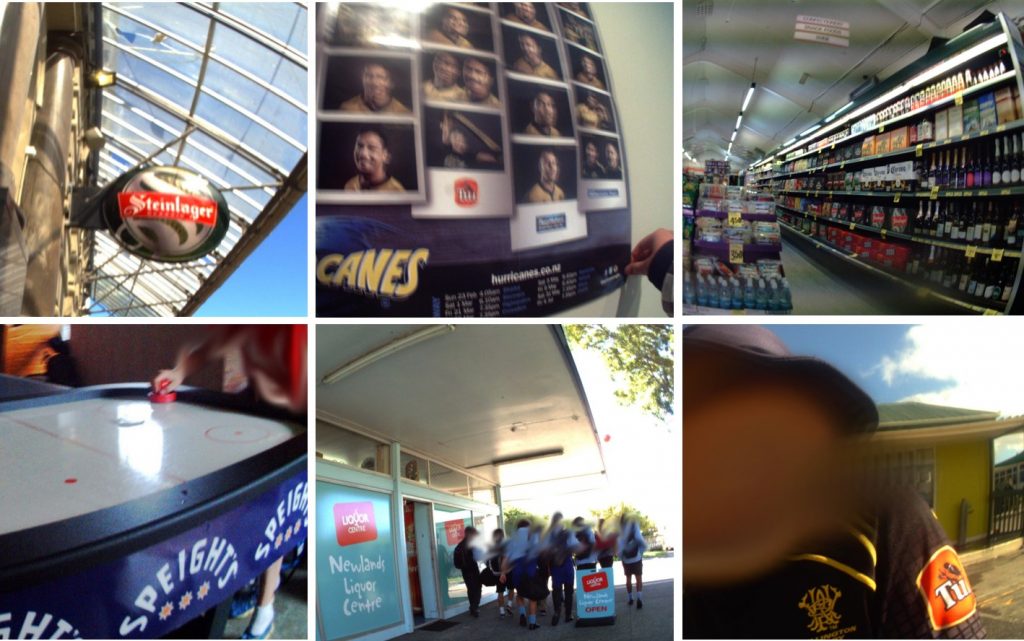

- Chambers T, Stanley J, Signal L, Pearson AL, Smith M, Barr M, Ni Mhurchu C.Quantifying the Nature and Extent of Children’s Real-time Exposure to Alcohol Marketing in Their Everyday Lives Using Wearable Cameras: Children’s Exposure via a Range of Media in a Range of Key Places. Alcohol and Alcoholism 2018;53:626-33.

- Chambers T, Stanley J, Pearson AL, Smith M, Barr M, Mhurchu CN, Signal L.Quantifying Children’s Non-Supermarket Exposure to Alcohol Marketing via Product Packaging Using Wearable Cameras. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs 2019;80:158-66.

- Chambers T, Pearson AL, Kawachi I, Stanley J, Smith M, Barr M, Mhurchu CN, Signal L.Children’s home and school neighbourhood exposure to alcohol marketing: Using wearable camera and GPS data to directly examine the link between retailer availability and visual exposure to marketing. Health & Place 2018;54:102-9.

- Andrew, D. Programmatic trading: the future of audience economics. Communication Research and Practice 2019;5:73-87, DOI: 10.1080/22041451.2019.1561398

- Carah N, Brodmerkel S. Alcohol marketing in the era of digital media platforms. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs 2020, in press.

- Niland P, McCreanor T, Lyons AC, Griffin C.Alcohol marketing on social media: young adults engage with alcohol marketing on facebook. Addiction Research and Theory 2017;25:273-84.

- Atkinson AM, Ross-Houle KM, Begley E, Sumnall H.An exploration of alcohol advertising on social networking sites: an analysis of content, interactions and young people’s perspectives. Addiction Research & Theory 2017;25:91-102.

- Griffiths R, Casswell S. Intoxigenic Digital Spaces? Youth, Social Networking Sites and Alcohol Marketing. Drug & Alcohol Review 2010;29:525-30

- Netsafe. New Zealand teens’ digital profile: A Factsheet. 2018. https://www.netsafe.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/NZ-teens-digital-profile_factsheet_Feb-2018-1.pdf.

- Noel J, Babor T, Robaina K.Industry self‐regulation of alcohol marketing: a systematic review of content and exposure research. Addiction 2017;112:28-50.

- Noel JK, Babor TF.Does industry self-regulation protect young people from exposure to alcohol marketing? A review of compliance and complaint studies. Addiction 2017;112:51-6.

- Gordon R, Harris F, Marie MacKintosh A, Moodie C. Assessing the cumulative impact of alcohol marketing on young people’s drinking: Cross-sectional data findings. Addiction Research and Theory 2011;19:66-75.

- Ratu R. Regulation urgently needed to protect Māori from alcohol advertising. New Zealand Medical Journal 2019;132:106.

- United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child. General comment No. 15 (2013) on the right of the child to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of health (art. 24). http://docstore.ohchr.org/SelfServices/FilesHandler.ashx?enc=6QkG1d%2FPPRiCAqhKb7yhsqIkirKQZLK2M58RF%2F5F0vHCIs1B9k1r3x0aA7FYrehlNUfw4dHmlOxmFtmhaiMOkH80ywS3uq6Q3bqZ3A3yQ0%2B4u6214CSatnrBlZT8nZmj

- New Zealand Law Commission. Alcohol In Our Lives: Curbing the Harm. Wellington, 2010. (Law Commission report; no. 114).

- Government Inquiry into Mental Health and Addiction. He Ara Oranga: Report of the Government Inquiry into Mental Health and Addiction. Wellington, New Zealand. 2018. www.mentalhealth.inquiry.govt.nz/inquiry-report/

- Health Promotion Agency. Alcohol-related attitudes overtime: Results from the Health and Lifestyles Survey, 2018. 2018. https://www.hpa.org.nz/research-library/research-publications/alcohol-related-attitudes-over-time-infographic.

- Health Promotion Agency. Alcohol-related attitudes – Results from the 2018 Health and Lifestyles Survey. 2019. https://www.hpa.org.nz/research-library/research-publications/alcohol-related-attitudes-results-from-the-2018-health-and-lifestyles-survey-infographic.

- Ministerial Forum on Alcohol Advertising & Sponsorship. Recommendations on Alcohol Advertising & Sponsorship. Wellington:Ministry of Health. 2014. (October). https://www.health.govt.nz/system/files/documents/publications/ministerial-forum-on-alcohol-advertising-and-sponsorship-recommendations-on-alcohol-advertising-and-sponsorship-dec14.pdf.

- Chambers T, Signal L, Carter MA, McConville S, Wong R, Zhu W. Alcohol sponsorship of a summer of sport: a frequency analysis of alcohol marketing during major sports events on New Zealand television. New Zealand Medical Journal 2017;130:27-33.

About the Briefing

Public health expert commentary and analysis on the challenges facing Aotearoa New Zealand and evidence-based solutions.

Subscribe

Public Health Expert Briefing

Get the latest insights from the public health research community delivered straight to your inbox for free. Subscribe to stay up to date with the latest research, analysis and commentary from the Public Health Expert Briefing.