Summary

Aotearoa New Zealand (NZ) has had high rates of community antibiotic dispensing for many years, much of it for patients with self-limiting viral respiratory tract infections, for which antibiotic “treatment” provides no benefit.

An unavoidable consequence of the high rate of community antibiotic use in NZ is that the prevalence of antibiotic resistance in common bacterial pathogens is much higher than in other countries where antibiotics are less frequently prescribed for illnesses for which they provide no benefit.

Influential healthcare leaders in NZ, such as Te Whatu Ora and the Royal New Zealand College of General Practitioners, should set goals to strongly encourage sustained cumulative reductions in inappropriate antibiotic prescribing. Evidence from other countries shows that large reductions in community antibiotic use can be achieved without adverse consequences.

Failure to dramatically reduce inappropriate antibiotic prescribing in NZ will impose a high cost in increased death and disability from untreatable bacterial infections in the coming decades. This cost will inevitably fall hardest on those communities with the highest overall rates of antibiotic use, currently Pacific and Māori whānau.

The problem of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) covers resistance to all drugs used to treat microbial infections, including antibiotics, antifungals, and antivirals. This article focuses on the relentless evolution and spread of antibiotic resistant bacteria which is an increasing threat to our ability to effectively treat many bacterial infections.

Most antibiotics were discovered and developed during the 20th century but in recent decades very few new antibiotics have been developed.1 Unfortunately, the low financial rewards from development of new antibiotics are not sufficient to encourage pharmaceutical companies to expand their efforts to develop new antibiotics. As antibiotic resistance becomes more common infections caused by antibiotic resistant bacteria will increasingly cause death and disability, as they did in the pre-antibiotic era.2

Antibiotic resistance occurs because antibiotic use kills or inhibits the growth of susceptible bacteria but allows resistant bacteria to thrive and spread. The magnitude of this effect varies between bacterial species, and between antibiotic medicines. For example, when penicillin first became available in the 1940s, it was able to kill more than 99.9% of Staphylococcus aureus bacteria, the common cause of boils, styes, and infections of damaged skin. Now, 90% of S. aureus bacteria are resistant to penicillin. S. aureus bacteria have gone on to develop resistance to many other antibiotics, and methicillin resistant S. aureus (MRSA) bacteria are an increasing cause of death worldwide.3 (see Appendix for further background).

It is a very common belief that antibiotic treatments which are prescribed by a doctor, and are taken for the recommended number of days, do not contribute to antibiotic resistance. This is a myth. All antibiotic treatments lead to a marked reduction in the number of antibiotic susceptible bacteria throughout a person’s body, while the antibiotic resistant bacteria multiply to higher concentrations. The increased density of antibiotic resistant bacteria on and in the treated person results in an increased risk of spread from the treated person to other people. People who have received antibiotics have a markedly increased rate of infection caused by antibiotic resistant bacteria for many months after the treatment course.4 Furthermore, their household members and members of their community are also at increased risk of colonisation and infection caused by antibiotic resistant bacteria – even if they haven’t taken antibiotics themselves.5,6 The unavoidable consequence is that communities with high rates of antibiotic treatment have high rates of infections caused by antibiotic resistant bacteria.

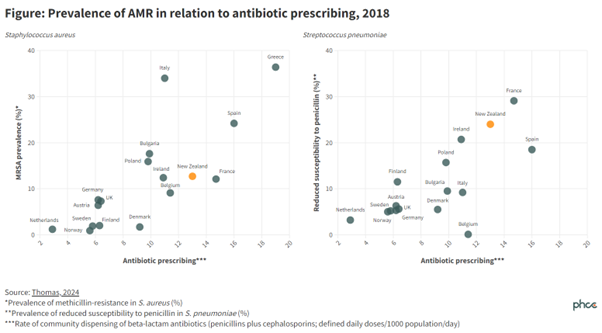

For many years, when compared with all other European nations, the overall community rate of antibiotic treatment has been very high in Greece and very low in the Netherlands and Sweden. Not surprisingly the rates of infections caused by antibiotic resistant bacteria have been high in Greece and low in the Netherlands and Sweden.7

Unfortunately the overall rates of community antibiotic use in NZ have been high for many years and in consequence we have high rates of antibiotic resistance.7 Figure 1 shows that the relatively high community rates of dispensing of penicillin and cephalosporin antibiotics in NZ have led to relatively high rates of reduced sensitivity to penicillin in Streptococcus pneumoniae (the most important cause of pneumonia, otitis media and bacterial meningitis) and high rates of methicillin resistance in S. aureus.

A large proportion of community antibiotic use in NZ, perhaps as much as half, is for people who have self-limiting viral respiratory infections such as coughs, colds, and sore throats, that pose essentially no risk of harm, and that are not improved by antibiotic “treatment”.

We should aim to rapidly reduce our rates of futile antibiotic prescribing for these self-limiting viral infections. A recently launched website (Antibiotic Conservation Aotearoa) provides a wide range of user-friendly resources to encourage reduced rates of antibiotic prescribing for people with upper respiratory tract infections such as sore throat, colds, otitis media, and cough.8

However, a similarly large proportion of community antibiotic use in NZ is to treat bacterial infections that may have a significant impact on the health of the unwell person. Any reductions in this antibiotic use may harm the health of the unwell person. And there are some conditions for which increased antibiotic use could significantly improve the health of people in NZ. For example, the persistently high rates of rheumatic fever,9 and of admission to hospital for skin and soft tissue infection, in Pacific and Māori children,10 suggest a need for better targeted community antibiotic treatment of Streptococcus pyogenes pharyngitis and for bacterial skin infections.

As discussed in a recent article in the New Zealand Medical Journal, rapid large reductions in rates of community antibiotic dispensing have occurred in many other countries when highly respected and influential national organisations have set ambitious goals for reductions in community antibiotic prescribing.7 Similar reductions in total antibiotic prescribing rates could be readily achieved in NZ, if prescribers committed to prescribing antibiotics only for patients with conditions in which antibiotics provide a health benefit. Such an approach would require prescribers to explain to their patients that while antibiotic “treatment” provides no benefit for viral respiratory infections, it commonly causes adverse effects, and inevitably promotes the spread of antibiotic resistance.

The need to reduce unnecessary antibiotic prescribing has been highlighted by a number of national and international organisations over the past decade. The table below links to several examples.

While Te Whatu Ora and the Royal New Zealand College of General Practitioners have expressed support for efforts to reduce unnecessary antibiotic use in NZ,11,12 neither organisation has provided strong leadership for change. It is long past time for both these organisations to actively encourage significant reductions in inappropriate antibiotic prescribing in NZ.

NZ should review its systems for managing and monitoring antimicrobial prescribing and AMR to identify useful improvement. For example, there is international evidence showing that levels of AMR are associated with AMR governance arrangements, for example across European counties.20 There is an opportunity for NZ to learn from best international practice in such areas.

What this Briefing adds

- Antimicrobial resistance poses a growing threat to public health both in NZ and globally.

- Rates of community antibiotic use in NZ have been high for many years.

- Reducing the inappropriate prescribing of antibiotics—for example, to treat viral respiratory infections—can safely reduce the spread of antimicrobial resistance.

Implications for policy and practice

- Influential healthcare leaders in NZ, such as Te Whatu Ora and the Royal New Zealand College of General Practitioners, should set goals to reduce inappropriate antibiotic prescribing.

- NZ should review its AMR governance to identify opportunities for ‘best practice’ improvements.

Authors details

Assoc Prof Mark Thomas, Faculty of Medical and Health Sciences, University of Auckland

Assoc Prof Stephen Ritchie, Faculty of Medical and Health Sciences, University of Auckland

Dr Juliet Elvy, Clinical Microbiologist, Institute of Environmental Science and Research (ESR)

Dr Kristin Dyet, Senior Scientist, Health and Environment, Institute of Environmental Science and Research (ESR)

Appendix: Antimicrobial resistance

Antibiotics are medicines that effectively treat infections caused by bacteria. They greatly increase the probability of surviving severe bacterial illnesses such as pneumonia, meningitis and peritonitis. They are also very useful for preventing bacterial infections that might otherwise occur following major surgery, or in people whose treatment to control cancer or other diseases may drastically weaken their immune defences and increase their risk of severe infections.

A huge number of bacterial species commonly live on the skin and in the intestines of humans, where they usually cause no harm, and often contribute greatly to the health of the colonised person. Even without intimate contact these colonising bacteria are readily spread from person to person, so that all residents of a home usually are colonised by similar populations of bacteria.5 A small proportion of the bacterial species that colonise humans can escape from the skin or intestines and infect other tissues, such as the lungs, or damaged skin, or bladder, and cause harmful infections in these sites.

The very fast reproductive rate of bacteria, many of which double in number every 20-30 minutes, allows for the rapid evolution and spread of mutant bacteria that have a survival advantage. Mutant bacteria that have a survival advantage arise relatively infrequently, but once they have arisen they often spread rapidly to outnumber their ancestral predecessors.

When a person takes an antibiotic the effect of the antibiotic is not limited to the site of the infection, nor to the bacterial species causing the infection for which the antibiotic was prescribed. Instead, the effect of the antibiotic treatment occurs throughout the body and is just as great for all the many species of bacteria that colonise the patient’s skin and intestines, as for the bacteria causing a harmful infection in some other organ. Antibiotic treatment of a sore throat, a bladder infection, or an infected finger will dramatically, and often for several months, throughout the body, reduce the proportion of colonising bacteria that are susceptible to the antibiotic and increase the proportion of bacteria that are resistant.5