The NZ Government’s recently released Standardised Packaging Regulations contain some important advances over Australia’s legislation, but they also miss opportunities to recognise tobacco industry innovations. This blog discusses changes that establish a new benchmark and why these are important, but also examines how the regulations could have gone further and suggests measures that other countries might consider including as they develop their standardised packaging policies.

Plain (or standardised) packaging has been in place in Australia since late 2012, and early evaluations already show knowledge of how smoking’s harms has increased while the appeal of smoking has declined. Despite desperate attempts by tobacco companies to manufacture an illicit trade problem, the empirical evidence shows this heavily promoted adverse outcome has not eventuated.1 2 Instead, predicted outcomes have emerged even earlier than hoped: quit attempts have increased,3 smoking prevalence has continued to decline, while never smoking has increased; as predicted young people seem to have been the main beneficiaries of this policy.4 5

The NZ Government’s slowness in adopting standardised packaging was disappointing but provided an opportunity to examine whether the Australian regulations had any loopholes, or if there were opportunities for improvement. So, how innovative and bold have New Zealand politicians been? The Ministry of Health has done well in developing regulations that advance those introduced in Australia; many changes are important and will undoubtedly curtail some of the tobacco industry’s responses seen in Australia. However, politicians could certainly have gone further and included new, evidence-based measures that would have increased the impact standardised packaging will probably have.

Brand and Variant Names

The Standardised Packaging regulations limit the length of brand names to no more than 50mm and specify a maximum font size (14 pt), while variant names are limited to 35mm and cannot use a font size larger than 10 pt. Tobacco companies may continue to use longer and more imaginative brand or variant names, but could have to use a smaller font to comply with the length restrictions; that is, tobacco companies may trade off brand and variant detail against the visual salience these attributes have. This step recognises that Australian tobacco companies have introduced increasingly evocative brand and descriptor names to try and recapture the connotations that brand imagery used to communicate.

This step is important, but could more have been done? The Government has missed the opportunity to disallow any new variant names or to limit the market to those brand and variant names that existed when the legislation was first introduced. Given the evidence that variant names have misled and deceived smokers6, and influenced choice patterns,7 the Government could also have allowed only standardised brand names to feature on packaging.

Stick Appearance

Many tobacco companies have responded to the requirement to feature warnings on packaging by creating cigarette sticks with appealing designs and embellishments. The new regulations constrain stick length (these may be no less than 7mm and no greater than 9mm in diameter, and no longer than 95mm) and thus prevent “slim” cigarettes, which have appealed to young women.8

However, options to go further were again possible; the regulations could have completely standardised stick dimensions, thus eliminating any points of differentiation between brands. They could also have introduced dissuasive sticks featuring unattractive colours or warning graphics, which give rise to unappealing connotations and are highly aversive.9 10 Because smokers actually consume sticks, this measure would have greatly reduced the appeal of sanitised and misleadingly “pure” looking white sticks by presenting tobacco as an unambiguously toxic product.

The new regulations require cigarettes to be cylindrical with flat ends; this requirement means innovations such as recessed filters are not allowed. However, filters still appear able to contain capsules that when squeezed, release a flavour into the cigarette; international evidence shows these innovations have proved popular among young people.11 Many smokers report their early experiences of smoking as unpleasant; just as alcopops offer young drinkers a highly appealing flavour that introduces them to alcohol, so capsule cigarettes offer young smokers a more palatable introduction to smoking. Failure to prevent this product innovation is a serious limitation in New Zealand’s regulations.

Pack Size and Interior

Importantly, the new regulations specify cigarette pack sizes (20 or 25 cigarettes) and roll-your-own (RYO) pouch weights (30g or 50g). This measure prevents inclusion of “bonus” sticks, used in Australia to change the value proposition offered to smokers; that is, tobacco companies can no longer provide additional sticks to compensate for reductions in pack attractiveness. Foil linings must also be fixed inside the pack (thus disallowing the pull out foil packs seen in Australia).

Preventing giveaway sticks is very important, particularly given New Zealand’s scheduled programme of excise tax increases, and the new warnings are welcome improvements. However, the regulations could also have required the drab green-brown colour that will feature on pack exteriors to be used on all internal pack surfaces currently coloured white. Such a change would have been especially important for RYO pouches, as many smokers roll their cigarettes on the clean, white pouch flap.

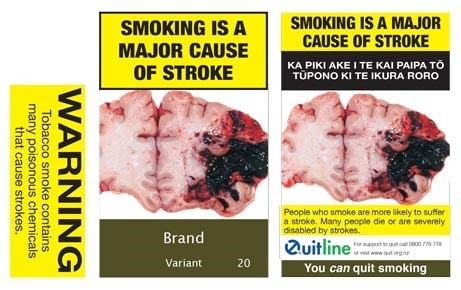

Warnings

The regulations also introduced a new suite of warning labels to replace existing warnings, which have been in place since 2008 and had lost effectiveness, and greatly enhanced the Quitline information and affirming cessation message.12

However, the regulations could also have created a larger set of more diverse warnings that recognise smokers’ heterogeneity, and ensured shorter rotation cycles.13 The Government should now establish a programme to support the rapid development and introduction of new warnings so these feature the most up-to-date evidence of smoking’s harms.

It is surprising to see that the new regulations did not require pack inserts, particularly given recent research found that reading of inserts increased over time (as reading of on-pack warnings decreased). Further, more frequent reading of the inserts was associated with greater response efficacy (i.e., stronger perceived benefits of quitting) and greater risk perceptions. More frequent reading of the inserts was also associated with greater self-efficacy to quit, increased quit attempts, and more sustained quit attempts.14

The regulations do not apply to the rolling papers and filters used to make cigarettes from RYO tobacco; these should also have been required to adopt standardised packaging, including pictorial warnings. RYO tobacco is popular among young people15 who develop ritualistic practices that add value to their smoking experience.16 Extending standardised packaging to all the components used to make RYO cigarettes would have more comprehensively reduced smoking’s appeal.

Conclusions

New Zealand’s Standardised Packaging Regulations close some important loopholes observed in Australia; these changes will benefit public health. However, failure to introduce evidence-based changes, such as dissuasive sticks and pack inserts, or to require the removal of variant names, mean the regulations miss opportunities to have greater impact. The small steps made in NZ’s regulations are important, but much larger leaps are required to achieve the Government’s Smokefree 2025 goal.