Summary

Energy costs for households are expected to rise significantly from 2025, due to a combination of factors putting pressure on Aotearoa New Zealand’s electricity system.

This is important because our poor-quality housing compared to other countries means we use more electric heating to keep warm and healthy over winter.

The evidence shows that those who can least afford to pay for electricity pay the most both per unit and relative to their income. Despite this, they still don’t meet their energy needs and as a result experience negative health and wellbeing consequences from cold housing.

It is essential that NZ’s lowest-income households can keep warm, so we must increase access to affordable electricity and energy efficient housing.

Energy poverty, when households are unable to afford or access sufficient energy to meet their needs at home, remains a critical public health concern. The health consequences of energy poverty cost the health system over $38 million per year due to cold, damp, and mouldy housing.1 As well as causing harm to physical health, energy poverty contributes to broader well-being impacts and increases the risk of severe mental distress.2 Living in energy poverty exposes many people to unsafe indoor temperatures. Low indoor temperature is a particular problem in NZ – evidenced by excess winter deaths compared to summer.3 A multi-country analysis found that in temperate countries like NZ, cold-related deaths outnumber heat-related deaths, and exposure to moderately cold NZ temperatures poses a greater risk than exposure to extreme cold.4 5 Living in poor quality housing and energy poverty forces people to make difficult ‘heat or eat’ trade-offs between energy use and other household expenses.

This Briefing uses information from the Household Economic Survey to estimate how many households were experiencing energy poverty in 2019.

How are electricity prices changing and what is the effect on households?

This winter has seen continued pressure on electricity supply in NZ, likely flowing through to increased prices for households next year.8 Residential electricity bills also include the cost of getting electricity to our homes, and price increases for the distribution and transmission component of electricity costs will reach households in April 2025, with rises of an estimated $10 - $20 per month.9 There is growing concern about electricity costs, with 67% of home owners expressing worry about their bills, up from 58% in 2022.10 Electricity affordability is straining households, with nearly half (45%) reporting significant financial pressure from electricity bills and the same number finding it harder to pay their electricity bills than a year ago. As a result, Consumer NZ estimated that 140,000 households had taken out a loan to pay their electricity bills, while 2% (38,000 households) reported having been disconnected because they couldn’t pay their electricity bill at least once in the past 12 months.11

We spend more on electricity when we can afford to

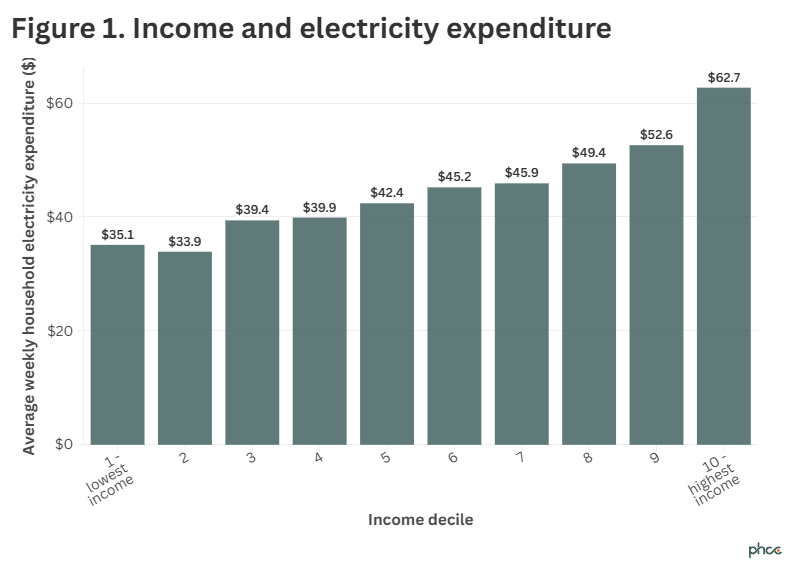

Looking at what households are spending on electricity gives another part of the picture. As income increases, expenditure on electricity also increases steeply (Figure 1).

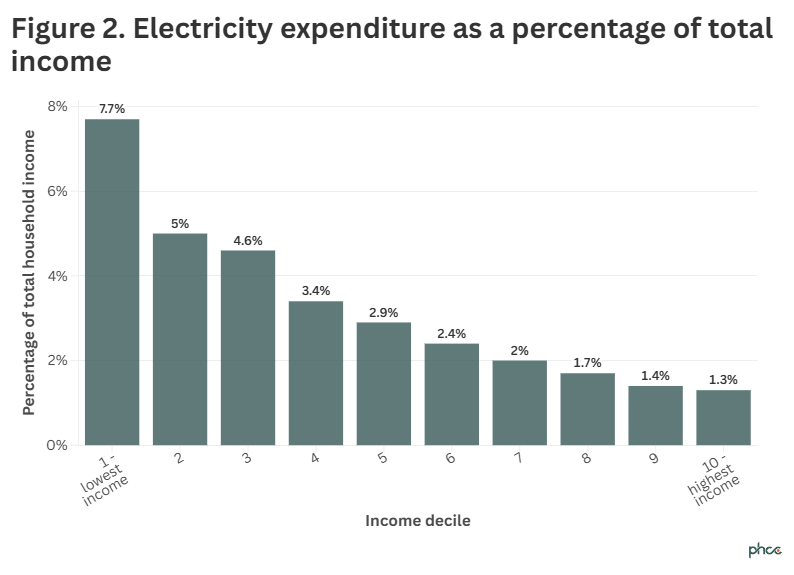

As a proportion of the total household income, the poorest households are spending over 7.5% of their income on electricity. The wealthiest 10% spend only 1.3% (Figure 2).

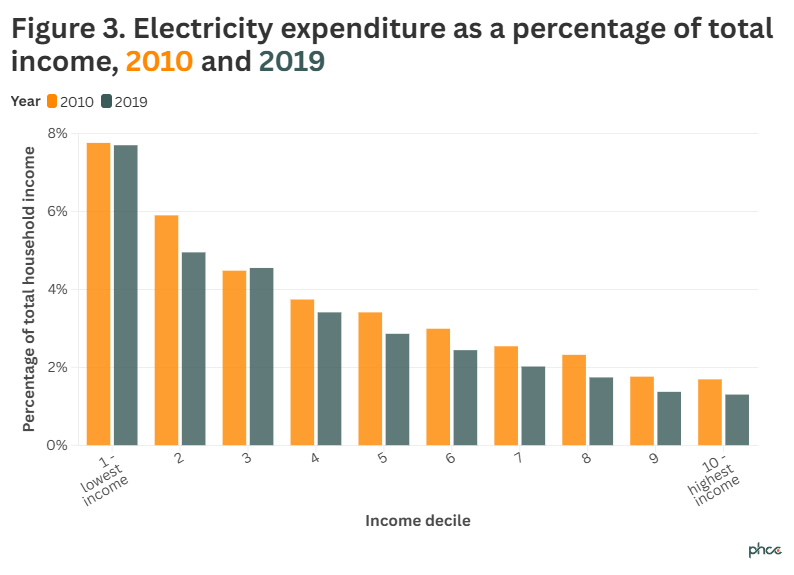

Between 2010 and 2019, those households with the lowest 10% of income have had almost no change in the proportion of income spent on electricity, while this has slightly decreased for most other income groups (Figure 3). Our research highlights that this is because those most vulnerable to energy poverty have already minimised electricity use: many report only keeping the lights and the fridge on—they are cutting back on washing, showering, cooking, and rarely or never heat their homes.12

Measuring population rates of energy poverty

The most commonly agreed method for estimating energy poverty across the population is to calculate how many households are spending twice the median proportion income on energy-related expenditure, known as ‘2M’.13 Using this measure and the 2018/2019 data from the Household Economic Survey, we find that before housing costs 16.37% of households were spending twice the median proportion on household energy. Extrapolating to the number of households in NZ, this is around 360,000 households. When we take housing costs into account, this jumps to 30.54%, or 595,000 households.

A better measure would include information about the thermal performance of housing, so that we know how much electricity would be needed to maintain comfortable and safe indoor temperatures of at least 18oC as recommended by the World Health Organization.14 Other countries have this information provided publicly at point of sale or rental through Energy Performance Certificate schemes.15 An Energy Performance Certificate in NZ would decrease information asymmetry in the housing market so that renters and buyers understand what the operating costs of homes are in the same way they understand the running costs of their cars. It would also enable targeting of policy towards improving the performance of homes to reduce energy poverty in the longer-term.

What this Briefing adds

- Using the best international measure of “2M” , at least 360,000 households were in energy poverty in NZ in 2018

- Accounting for housing costs, almost 600,000 households were affected.

Implications for policy and practice

- With increased pressures on cost of living after COVID-19 we expect that the number of households experiencing energy poverty is rising

- Continuing to monitor energy poverty will help to inform policy to support these households. Results from the most recent Household Economic Survey will be available soon.

- Continuing to improve home energy efficiency and making electricity cheaper for families is critical for addressing energy poverty, an important social determinant of health

- Information on the energy required to power our homes, available through energy performance certificates, would better able us to measure and address energy poverty in NZ

- To meet NZ’s nationally determined contribution to the Paris Agreement, it is essential to improve energy efficiency in low-income households, which will reduce emissions and have important co-benefits

Authors details

Dr Kimberley O'Sullivan, He Kāinga Oranga / Housing and Health Research Programme, Department of Public Health, University of Otago Wellington / Ōtakou Whakaihu Waka ki Pōneke

Zhiting Chen, He Kāinga Oranga / Housing and Health Research Programme, Department of Public Health, University of Otago Wellington / Ōtakou Whakaihu Waka ki Pōneke

Dr Caroline Fyfe, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden

Prof Nevil Pierse, He Kāinga Oranga / Housing and Health Research Programme, Department of Public Health, University of Otago Wellington / Ōtakou Whakaihu Waka ki Pōneke