References

- Reason J. Human error: models and management. BMJ. 2000 https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.320.7237.768

- International Civil Aviation Organisation. Safety Management Manual (SMM). Third Edition-2012 https://www.icao.int/sam/documents/rst-smsssp-13/smm_3rd_ed_advance.pdf

- Royal Commission on the Pike River Coal Mine Tragedy. 2012; Volume 2, pp29-30. Available from: https://pikeriver.royalcommission.govt.nz/vwluResources/Final-Report-Volume-Two/$file/ReportVol2-whole.pdf

- Office of the Minister for COVID-19 Response. Cabinet Paper: COVID-19 Resurgence: Improving Public Health Measures at Alert Level 1. 2020 Nov 16. https://www.dpmc.govt.nz/sites/default/files/2023-01/Paper-CP1-16112021-COVID-19-Resurgence-Improving-Public-Health-Measures-at-Alert-Level-1.pdf

- Grossman DC, Reay DT, Baker SA. Self-inflicted and unintentional firearm injuries among children and adolescents: the source of the firearm. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.153.8.875

- Violano P, Bonne S, Duncan T, et al. Prevention of firearm injuries with gun safety devices and safe storage: An Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma Systematic Review. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery. 2018 Jun https://doi.org/10.1097/ta.0000000000001879

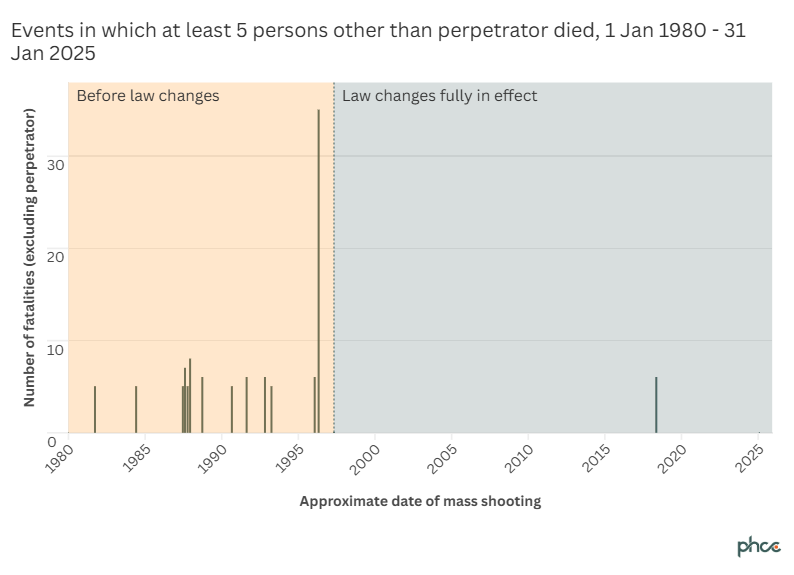

- Chapman S, Stewart M, Alpers P, Jones M. Fatal firearm incidents before and after Australia's 1996 national firearms agreement banning semiautomatic rifles. Annals of internal medicine. 2018 https://doi.org/10.7326/m18-0503

- European Commission: Directorate-General for Enterprise and Industry. Evaluation of the Firearms Directive : final report. Publications Office; 2014. https://doi.org/10.2769/89829

- Schell TL, Smart R, Cefalu M, Griffin BA, Morral AR. State policies regulating firearms and changes in firearm mortality. JAMA network. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.22948

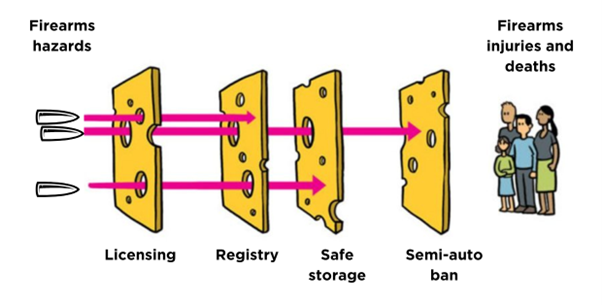

- The illustration is based on an image with the following credit: @Siouxsiew @Xtotl thespinoff.co.nz Adapted from James Reason, Ian Mackay, Sketchplanations CC-BY-SA 4.0. Original image available from: https://www.auckland.ac.nz/en/news/2020/10/22/covid-19-and-the-swiss-cheese-system.html

- Chapman S. Over our dead bodies: Port Arthur and Australia's fight for gun control. Sydney University Press; 2013.https://open.sydneyuniversitypress.com.au/files/9781743320310.pdf

- Ellis P. Poisson point processes, mass shootings and clumping. Free Range Statistics. 2019. http://freerangestats.info/blog/2019/09/07/mass-shootings-oz

- Chapman S, Stewart M, Alpers P, Jones M. Fatal firearm incidents before and after Australia's 1996 national firearms agreement banning semiautomatic rifles. Annals of internal medicine. 2018. https://doi.org/10.7326/m18-0503

- Council of Australian Governments. National Firearms Agreement. 2017 Feb [cited 2025 Feb 10]. Available from: https://www.ag.gov.au/sites/default/files/2022-09/crime-national-firearms-agreement.pdf [This paper uses the shorthand “Australian law” to refer to the National Firearms Agreement. The National Firearms Agreement is an agreement between the Australian Commonwealth and State governments on the minimum requirements for firearms laws implemented by the States (some laws related to firearms are Commonwealth laws). Not all States are in perfect conformance with the Agreement and some have introduced more stringent laws that go beyond the requirements of the Agreement. The complexities of the arrangement are beyond the scope of this note.]

- Council of Licensed Firearms Owners. Police Hid Truth About Terrorist Licensing, Inciting Needless Law Changes and Gun Buyback. Media Release. 2024. https://www.colfo.org/post/police-hid-truth-about-terrorist-licensing-inciting-needless-law-changes-and-gun-buyback

- Te Tari Pūreke. Licensing and Registry Snapshot. 2024. https://www.firearmssafetyauthority.govt.nz/sites/default/files/2024-02/firearms-public-dashboard-january2024.pdf

- Thorp T. Review of Firearms Control in New Zealand: Report of an Independent Inquiry, commissioned by the Minister of Police. GP Print, Wellington. 1999. https://www.police.govt.nz/resources/1997/review-of-firearms-control/review-of-firearms-control-in-new-zealand.pdf

- Savage J. 'Terrorist attack': How police thwarted heavily armed teen's plan to shoot teachers, classmates in South Island school. NZ Herald. 2020. https://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/terrorist-attack-how-police-thwarted-heavily-armed-teens-plan-to-shoot-teachers-classmates-in-south-island-school/UIBDQEDPD5OCWPJLYN34DSI53U/

- Ministry of Justice. Arms Act rewrite: Discussion Document. 2025. https://consultations.justice.govt.nz/policy/public-consultation-on-the-arms-

About the Briefing

Public health expert commentary and analysis on the challenges facing Aotearoa New Zealand and evidence-based solutions.

Subscribe

Public Health Expert Briefing

Get the latest insights from the public health research community delivered straight to your inbox for free. Subscribe to stay up to date with the latest research, analysis and commentary from the Public Health Expert Briefing.