Summary

After two years operation, the Public Health Communication Centre (PHCC) and the Public Health Expert Briefing are established sources of science-based commentary in Aotearoa New Zealand. We have built on our successful first year with increasing numbers of Briefing articles, contributing authors, subscriber numbers, and media coverage, indicating support for the PHCC as an independent voice.

Analysis of topics covered by our first 150 Briefings shows a wide breadth, with a particular focus on responding to emerging threats such as epidemic and pandemics, and informing policy debates around control of tobacco, improving nutrition, and housing. Briefings have contributed to all phases of the policy cycle, with a particular focus on agenda setting and policy formulation.

Important directions for the future include an increasing focus on decision-making, including scrutiny of processes to ensure they are transparent and address the commercial determinants of health, and more evaluation of policies and programmes.

As the Public Health Communication Centre (PHCC) celebrates its second anniversary, we take this opportunity to reflect on our effectiveness and look ahead to the future. Since our launch in early 2023, the PHCC has worked actively to highlight critical public health research and opportunities to improve health, equity, and environmental sustainability.1

This review focusses on the Public Health Expert Briefing (The Briefing), which is our major output. Here we describe the scope of topics covered, how our articles address key stages in the policy cycle, the reach of this publication, and expand on our previous review of the first year of operation.2

Two years of the Public Health Expert Briefing

The Briefing is an online publication written by public health researchers and practitioners. It is quality assured and indexed by Google Scholar and Google News, making content highly accessible.

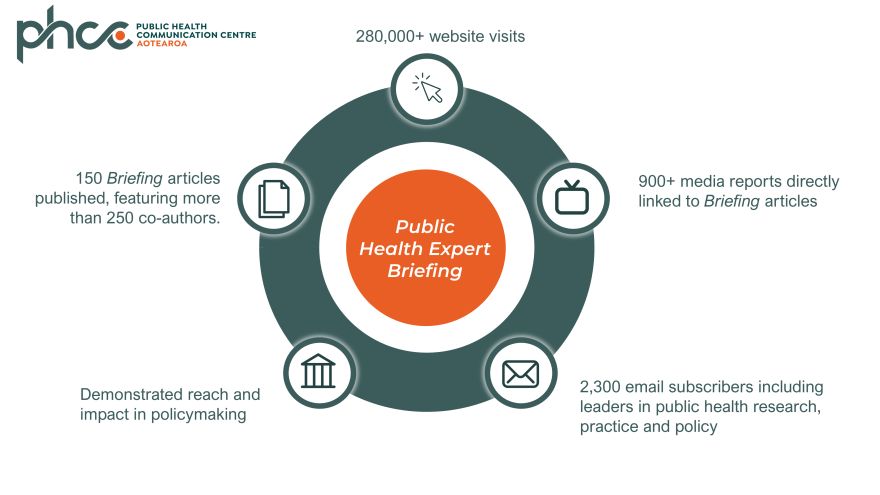

The 150 Briefings published to date reach significant audiences (Figure 1). These articles cover a wide range of topics (Figure 2) focussing on pressing public health issues, with an emphasis on policy-level change rather than individual behaviour shifts. Our goal is to address the systems and structures that drive population health outcomes.

The Briefing has also been a major source of media content (Figure 1). Our tracking shows that more than 900 media stories have directly referenced articles from the Briefing—a likely undercount of its wider influence.

Beyond media impact, the Briefing fosters collaboration across the public health community. More than 250 unique authors have contributed articles, with many co-authored by teams from multiple institutions. This collaborative approach strengthens networks and amplifies diverse voices.

Figure 1. Key metrics for Public Health Expert Briefing and PHCC engagement

Topics and areas covered by The Briefing

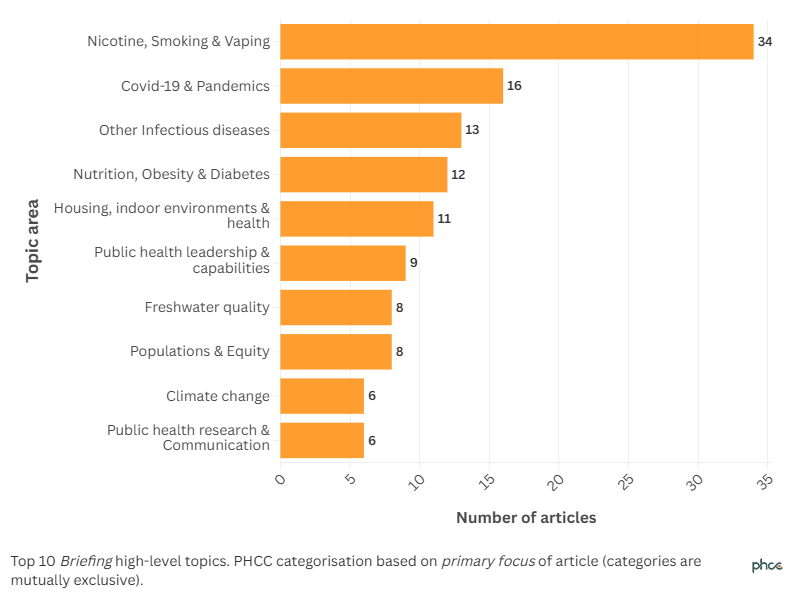

We have grouped Briefing topics into 20 broad areas (Figure 3 and Appendix). The most frequent topics reflect responses to pandemic threats3and epidemic threats such as measles.4 There were also responses to major policy changes such as repeal of Aotearoa’s world leading smokefree legislation5 and threats to Ka Ora, Ka Ako, the Healthy School Lunch Programme.6

Figure 2: Word cloud showing most frequent words from the first 150 Briefings

Figure 3: Number of Briefing articles by primary broad topic area, showing the top 10 categories, Feb 2023 to Feb 2025

Classifying articles using a single topic area only partially captures their meaning and implications. For example, the PHCC is committed to honouring Te Tiriti o Waitangi by embedding equity and partnership into our work. We actively encourage Briefing authors to reflect on the implications for Māori health and provide a platform for Māori researchers. To date, just under half of our Briefings (44.4%) specifically address inequities faced by Māori across various public health issues. And a third of our Briefings (30.4%) have at least one Māori author.

Using the Policy Cycle to identify the contribution of Briefings

The Briefing’s content can be examined through the lens of the Policy Cycle, a framework that outlines the steps involved in creating and implementing effective policies.7 Our articles have addressed every stage of this cycle, though not all to the same extent.

Most articles have focussed on putting public health issues on the policy agenda (eg, human health impacts of plastic exposure8) or suggesting ways in which policy responses could effectively address these public health threats and opportunities (eg, the role of food and beverage taxes for a healthier diet9).

A smaller number focussed on decision-making, particularly highlighting opportunities to make submissions (eg on the Emissions Reduction Plan10). Some also examined the policy making process itself (eg tobacco industry influence11).

Far fewer articles were focussed on responding to evidence about implementation (eg, importance of delivering vaccine during pregnancy12) and evaluation of policy responses and interventions (eg, evaluation of the Warmer Kiwi programme13). This situation probably reflects the limited amount of evaluation research being conducted in NZ, a situation that should change if we want better evidence-informed public health policies and programmes.

Figure 4: Distribution of Briefings approximately classified according to the phase in the policy cycle where they were particularly focussed

Looking Ahead

As the PHCC enters its third year, we remain committed to our purpose, which is:

“To effectively communicate public health research evidence to protect and improve the health, well-being, and equity of the people of Aotearoa New Zealand and the health of the environment in which we live”.

Many of the major public health threats remain or are increasing, notably climate change/extreme weather events, biodiversity loss, misinformation, pollution, infectious diseases, pandemic risks, and armed conflict.14

The capacity for evidence-informed policy is also threatened by downsizing of Government agencies, universities and the science sector. Similarly, the size of mainstream media which disseminate such information while generally adhering to codes of practice is reducing. This gap leaves social media as the main news source for many, but with decreasing content scrutiny and fact checking.

To ensure our work remains relevant, we will continue to choose topics with good potential for impact. This means selecting areas where the public health burden is relatively high and there are interventions that are effective, affordable and acceptable (eg, cardiovascular disease).15 It is important to encourage submissions on issues which have reached the decision-making stage (eg, suicide prevention plan16). We also need to emphasise proactive issues where long-term action is critical (notably climate change).17

As a further check on our focus, we will continue efforts to engage with key stakeholders and collaborators. This process can include the use of surveys and consultation with the public health community to identify priorities and areas of potential positive change. The PHCC will also continue fostering partnerships and amplifying diverse voices to address the most pressing public health challenges.

Trust in science remains high in NZ, with strong support for scientists being involved in policy decisions and researching public health.18 The PHCC will work to maintain and increase that trust.

What this Briefing adds

- Briefing articles have covered a wide range of public health subject areas, with a particular focus on responding to emerging threats such as epidemics and pandemics, and major policy debates on issues such as tobacco control and improving nutrition.

- Briefings have contributed to all phases of the policy cycle, with a particular focus on agenda setting and policy formulation.

Implications for policy and practice

- A policy cycle analysis suggests that NZ may need to conduct more research to evaluate the delivery of interventions and their impact to better inform policy processes.

- Future Briefings could focus more on opportunities for input during the decision-making process and analysis of how that process can become more open and democratic.

Implications for readers

- To stay up to date on the latest research and commentary from the PHCC, please subscribe and get new articles delivered straight to your inbox.

- If you are a public health researcher or practitioner interested in contributing a Briefing article, please get in touch.

- If you have any feedback on the Centre, the Briefing, and how we can better inform advances in public health, please let us know.

Authors details

Prof Michael Baker, Dr John Kerr, Adele Broadbent, Prof Simon Hales, Marnie Prickett, Fiona Taylor, and Prof Nick Wilson are all staff of the Public Health Communication Centre and Department of Public Health University of Otago, Wellington.

Acknowledgements

We want to take this opportunity to thank all the authors who have contributed their time and expertise to the Briefing. We also thank the Public Health Expert Briefing Editorial Board: Richard Edwards, Emma Rawson-Te Patu, Cristina Cleghorn, Kim O’Sullivan, Tim Chambers, and Helen Eyles; and the PHCC Advisory Board: Dacia Herbulock, Anaru Waa, Peter Griffin, Teresa Wall, Boyd Swinburn and Richard Sutherland.

Appendix: Additional information on the classification of Briefing articles

Topic areas covered

This classification of articles aimed to identify the dominant intent of the article and assign a specific topic. Most topics focussed on health threats (eg, smoking, vaccine preventable diseases). Some focussed on populations (eg, children and youth), or processes (eg, public health surveillance).

To make the analysis more manageable, these topics were then grouped into broad areas covering closely related topics (eg, Public health policy, Decision-making, and Infrastructure were grouped into Public health leadership & Capabilities) (Table 1).

Table 1. Number of Briefing articles exclusively classified by broad topic area, Feb 2023 to Feb 2025

| Broad area | Frequency |

| Nicotine, Smoking & Vaping | 34 |

| Covid-19 & Pandemics | 16 |

| Other Infectious diseases | 13 |

| Nutrition, Obesity & Diabetes | 12 |

| Housing, indoor environments & health | 11 |

| Public health leadership & capabilities | 9 |

| Freshwater quality | 8 |

| Populations & Equity | 8 |

| Climate change | 6 |

| Public health research & Communication | 6 |

| Natural hazards & Disasters | 5 |

| Other environmental health | 5 |

| Injuries | 4 |

| Transport, Energy & Health | 4 |

| Alcohol & Drugs | 3 |

| Maori health & Equity | 2 |

| Mental health & Suicide | 2 |

| Cancer | 1 |

| Other Long-term conditions | 1 |

| Total | 150 |

Major areas of focus included:

- Nicotine, Smoking & Vaping – Reflecting the strong evidence base for policies to combat highly addictive nicotine products, notably Aotearoa’s world leading smokefree legislation repealed under urgency on 28 February 2024 by the incoming Coalition Government

- Covid-19 & Pandemics – Reflecting the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic, the rising threat from highly pathogenic avian influenza, and the need to increase pandemic preparedness

- Other Infectious diseases – Reflecting the ongoing need to improve immunisation coverage to prevent and minimise vaccine preventable diseases such as pertussis/whooping cough and measles along with other emerging threats such as congenital syphilis

- Nutrition, Obesity & Diabetes – Reflecting the importance of healthy nutrition as a key health determinant and the evidence favouring retention of Ka Ora, Ka Ako, the Healthy School Lunch Programme

- Housing, indoor environments & health – Reflecting the multi-faceted role of housing as a key health determinant

Policy cycle applied to public health

This classification of articles aimed to group them according to the broad intent of the article. The position on the policy cycle also depended on how mature the issues was, with some issues potentially being at multiple points on the cycle. Below is a description of how we have defined these stages along with examples of Briefing articles.

Agenda setting – Identifying a public health problem or opportunity that requires a government or societal intervention and proposing it as an issue. Arguably, all policy engagement involves agenda setting, but the scope here is concerned with new public health problems and opportunities that have not already been identified as requiring a policy response and been placed on the agenda. This stage may overlap with evaluation (stage 5) if it draws on the lack of success of current policy settings. These topics may include:

- concepts that can significantly advance public health, eg long-term thinking and a strong focus on reducing health inequity

- novel threats, eg, potential new pandemics and the potential health impact of new technology such as AI

- threats that have been newly recognised, eg, plastic pollution

- problems that have been neglected in the past, eg, carcinogen exposure in workplaces

- increases in population vulnerability, eg, rise in aging and dementia

- advances in interventions and evidence to improve public health, eg, benefits of improved nutrition in pregnancy and the growing evidence that masks work

Policy formulation – Setting objectives to address an identified public health problem or opportunity and active consideration of alternative actions to achieve those objectives. This stage may overlap with agenda setting (stage 1), as sometimes reviewing objectives and alternative actions can put a public health problem back on the agenda for action. Similarly, this stage may overlap with evaluation (stage 5) if it draws on the lack of success of current policy settings. The policy formulation process can include:

- describing rational approaches and criteria for evaluating public health policy options and choosing an optimal response, eg, cardiovascular disease

- using evidence systematically to suggest new or stronger objectives for addressing a public health problem, including making the issue a higher priority, eg, stronger responses to major natural disasters, or oral nicotine products or new waves of Covid-19

- using evidence systematically to suggest new or different interventions, including proximal causes and distal determinants, eg stronger focus on reducing child poverty and healthy food policies

- using international comparisons about performance and league tables suggesting a more effective response is needed, eg, leaks and water infrastructure (potentially stage 5 if part of a systematic evaluation)

Decision making – Prioritising, negotiating and deciding on policies, programmes, and legislation that will proceed, often based on a combination of policy aims, political concerns, and constraints of resources and capabilities. Includes public health input into decision making about the response to a current issue. Decision making (stage 3) can overlap with policy making (stager 2). These processes can include:

Implementation – Delivering a proposed policy, based on clear articulation of the solution, allocation of resources, delegation of decision-making authority and infrastructure to support delivery and legislative or regulatory changes. Includes public health consideration of evidence about effective and equitable delivery of a policy or programme. These processes can include:

Evaluation – Measuring the impact of the policy, programme or legislation and identifying areas for improvement. Includes public health consideration of evidence about the impact, success or failure of a current policy or interventions and implications. These processes can include:

- identifying criteria for assessing successful policies and programmes and how to measure them

- conducting a formal evaluation (eg, trial) of an intervention or programme on the outcomes of interest, eg, evaluation of a Long Covid clinic for health workers

- systematic review of current practice and its effectiveness for achieving the outcome of interest and identifying opportunities for improvement to existing policy or programme, eg, evaluation of the Warmer Kiwis programme

Other – Articles that are not concerned with the policy process or are concerned with it in totality. For example:

Table 2. Number of Briefing articles exclusively classified by broad policy cycle phase, Feb 2023 to Feb 2025

| Policy cycle phase | Frequency |

| Agenda setting | 59 |

| Policy formulation | 65 |

| Decision making | 16 |

| Implementation | 4 |

| Evaluation | 3 |

| Other | 3 |

| Total | 150 |