Summary

Budget 2024 emphasises tax cuts, funded by spending reductions and increased borrowing, amid a recession. This situation results in reduced funding for health determinants, including health care, education, welfare, housing, environmental protection, and law and order, shrinking relative to GDP over the next three years.

Public health, which requires long-term investments in areas like child poverty and housing to prevent future health issues, faces challenges due to the budget’s short-term focus.

Public health professionals must prioritise effective programs within limited funding and increase public understanding of the value of long-term health investments. Despite the tougher environment, their role in prioritising community health and future generations remains crucial, even as the budget constraints complicate their efforts.

Budget 2024 was very much about tax cuts (as promised in the 2023 general election), funded by spending reductions and increased borrowing. It was all made harder because the New Zealand economy is in a recession, which reduces tax revenue and increases some spending (like unemployment benefits when people lose jobs).

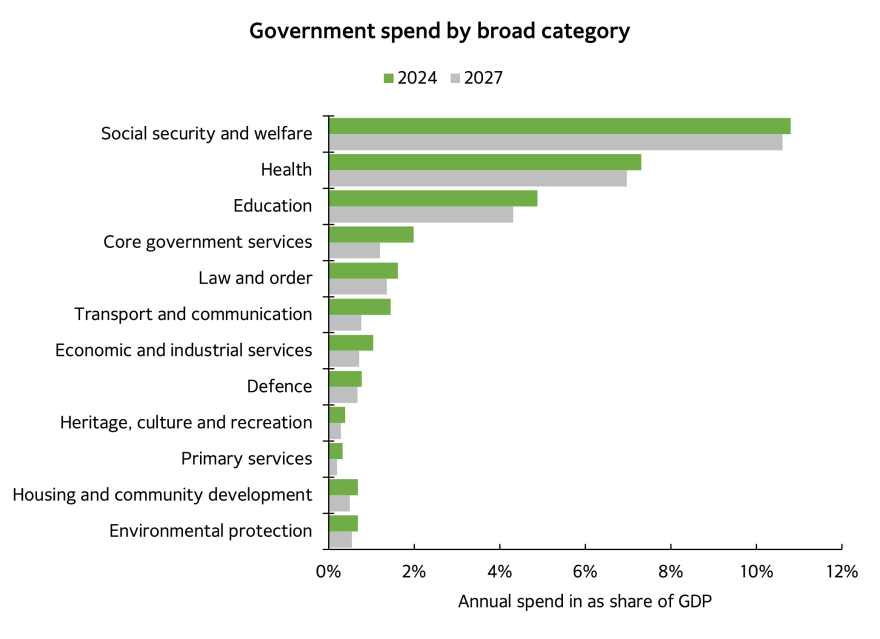

The spending cuts were widespread. When compared against GDP (to crudely account for population, prices and incomes), every broad area of spending is forecast to shrink over the next three years, led by cuts in the core government service (an election promise), and even health and education (not an election promise). Future operating allowances are too small to cover existing service levels relative to population and inflation.

The tax cuts will accrue mostly to higher income households and those with children in Early Childhood Education. A poor household will receive an income tax cut worth around 0.5% while a high income earner more like 2%. These are insufficient to have a meaningful impact on health.

So what does the budget mean for the Public Health sector? Below, I lay out the context, the budget headlines and consequences, and some ideas for Public Health professionals.

Context: public health is the right but hard thing to do

Health spending is mostly seen through an acute care lens (hospitals, GPs and medicines), rather than public health. This is unsurprising. Funders and politicians want results within timeframes for which they can take credit.1 This has led to health being predominantly the domain of disease, treatment, and medicalisation of society.

Public health is seen as costs now benefits later.

Public health measures often require investments in an unrelated area (say housing), for avoided health care costs in the future. Public Health is at odds with the expectations of politicians and the public, and the way our public sector is set up, where they compete for available funding (for example, money allocated to more medicines may mean less funding for problem debt and social housing).

There is no easy way for the Ministry of Housing and Urban Development to make a claim on future avoided health costs for better housing today.

The social investment approach championed by then finance minister Bill English was meant to solve this problem. Some progress was made, for example through the Whanau Ora model, which devolved funding closer to those affected and allowed for a wider range of responses.

But the overall funding envelope did not increase to accommodate this new focus. Rather than an investment (which means an injection of capital), it was a reallocation of current resources from the poor to the very poor, which unfortunately but predictably simply created a new cohort of very poor.

A worked example might help. Avoided cardiovascular disease saves $10,435 a year, according to the Treasury’s CBAx tool. Assuming a person lives with cardiovascular disease for 36 years2, the net present value of avoiding the disease is just over $173,000 today. That is, we would be indifferent between spending $173,000 today on a range of measures (which might include income support, nutrition, and housing) against the cost of that person living with CVD in the future.

The practical political difficulty of course is that $173,000 is not currently available today (or in a programme over say a decade) to avoid future costs. Nor is there much appetite among the public to admit that the government services they enjoyed in the past may have been misallocated, or that the tax they paid in the past was insufficient to fund investment programmes and activities that would have reduced health burdens today. We are all culpable. And importantly, it means that public health does not feature in a Budget as a line item or a focus of inquiry, rather it is woven through the broader whole.

Budget 2024: less revenue, less spending

The centre-piece of Budget 2024 is less revenue and less spending. The implications for public health are two fold:

- there is less money for clearly identified health programmes, and

- there is less money for the wider social determinants of health, especially those who are poor and at the margins of society.

The analysis here is at the high level rather than programmes, which would require much greater level of inquiry than available for this opinion column. The Budget sets the spending envelope, but it doesn’t give us much detail of what will be funded and how it will be spent.

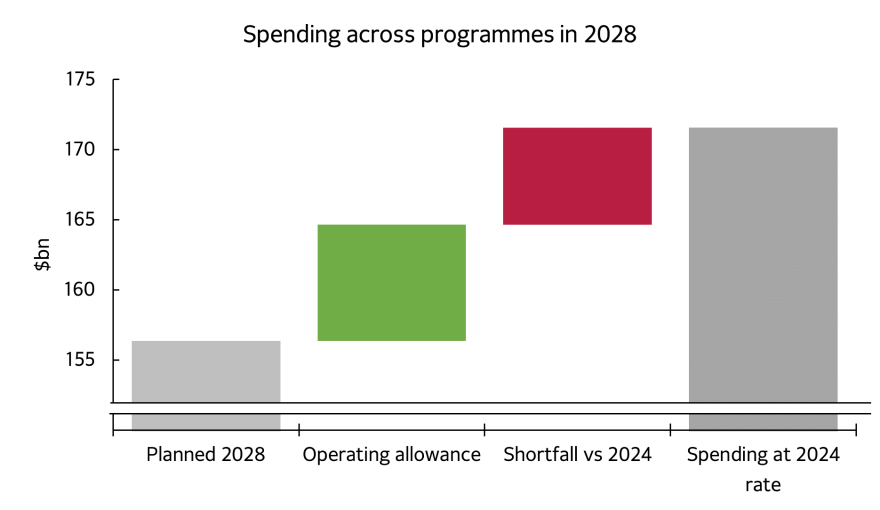

Each budget also sets allowances for future spending decisions. Budget 2024 adopted a very small spending allowance, which is unlikely to be enough to keep up with demand growth from a growing and ageing population, and cost increases. By 2028, government spending is intended to fall from 33% of GDP in 2024 to 31% in 2028.

WHO provides a pretty long list3 of the social determinants of health: Income and social protection; Education; Unemployment and job insecurity; Working life conditions; Food insecurity; Housing, basic amenities and the environment; Early childhood development; Social inclusion and non-discrimination; Structural conflict; Access to affordable health services of decent quality. It illustrates the many threads that need to woven together in a cohesive whole to improve public health.

Crudely then, the areas of spending we are most interested in are health, education, welfare spending, housing, environmental protection, and law and order. Budget 2024 plans to spend less on each of these areas over the next three years.

Figure 1: Government spend is set to reduce across all areas, for the fiscal years 2024 and 2027 without operating allowances.

Source: NZ Treasury, Budget 2024

Figure 2: Operating allowances over the next 4 years are designed to reduce the size of government spending relative to GDP

Source: NZ Treasury, Budget 2024

Welfare policy change deserves a special mention, whereby payments will gradually become less generous, as they are indexed to CPI again, rather than wages, which usually increases faster. But Superannuation payments will remain indexed to wages, showing the inequitable way our welfare system treats universal superannuation for over 65s (who never paid enough taxes to fund future superannuation payments, they are paid out of current taxes) compared to those living in poverty.

This situation doesn’t mean there will be no spending on areas that affect public heath, nor does it mean that the programmes that are funded will be bad. But it does mean the envelope of funding available will shrink, and the public service will need to be particularly adept at prioritising that money to those efforts that have most impact.

Experience of previous political cycles suggests that shrinking services faced with increasing demand sees worsening outcomes, especially for those who are poor and vulnerable, and communities which are already deprived.

It is unclear if a shrinking and under attack public sector is up to the task of shrinking and becoming more efficient and effective at the same time. Those with experience of change management will know how difficult this will be.

Budget 2024 has set New Zealand on a path of reduced government services (or politically speaking, reduced government size) and a repeat of the 1980s belief that a smaller more efficient and more effective public sector will arise out of this. It seems unlikely given similarly failed experiments in our own past, or the most recent efforts by conservative governments in the UK.

Task for public health sector

The task ahead for the public health sector remains in some ways the same – weave together all those policies and programmes so that they don’t just medicate the sick (or sow seeds of ill health), but we improve health and wellbeing. The job is made harder because the many threads the sector works across will be in retreat, many public services will patch protect, and we will see less collaboration. We know that public health is the right thing to do, but it is hard to do.

These suggestions feel inadequate, but they are all I have to offer to public health professionals. Your job is two-fold:

- Continue to deliver excellent public health programmes within the funding available. Prioritisation is key – not all interventions are equal. Support each other in not only making the prioritisation, but also putting in place – where possible – systems to measure the impact of stopped or changed programmes and policies.

- Increase public understanding of the value of avoided costs. What the public currently consider intangible, distant, and unlikely to affect them, are in fact the opposite. It is not a task for Public Health professionals alone, but they have the best knowledge. Partnerships and collaborations will be key to not only create this knowledge, but to amplify and diffuse it through our communities in many years to come.

Public health is fundamentally about prioritising community and future generations above the individual today. Public health is dealing with a wider malaise in society, that of declining social cohesion. Budget 2024 is merely an expression of that. Our task remains important and valuable, but it just got harder.

What this Briefing adds

- Budget 2024 focuses on tax cuts funded by spending reductions and increased borrowing.

- There is underinvestment or reductions in spending for a range of areas that impact public health long-term.

Implications for policy and practice

- Public health professionals must continue delivering excellent public health programs within the available funding and work together to prioritise interventions and evaluate policy changes.

- They must also work to build greater public awareness of the need for long-term investment in public health in Aotearoa New Zealand.

Author details